On Puzzles, Privilege, and Missing Pronouns

When I read blogs by the parents of autistic children, I often happen across the puzzle metaphor. It finds its way into statements such as “My autistic daughter is such a puzzle” or “We’re still putting together the pieces of the puzzle that is my son.” I’ve always had a visceral response to the puzzle image to describe autism and autistic people, especially when used in the puzzle-piece logo of the Organization-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named. It’s so offensive on a gut level that I’m having difficulty even beginning to write about it.

When I read blogs by the parents of autistic children, I often happen across the puzzle metaphor. It finds its way into statements such as “My autistic daughter is such a puzzle” or “We’re still putting together the pieces of the puzzle that is my son.” I’ve always had a visceral response to the puzzle image to describe autism and autistic people, especially when used in the puzzle-piece logo of the Organization-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named. It’s so offensive on a gut level that I’m having difficulty even beginning to write about it.

A puzzle suggests the idea that there might be some pieces missing. Of course, such an idea is anathema to me, when applied to any person on the planet. The only way in which you could look at a person and see pieces missing is if you begin with a preconceived notion of what a person is supposed to look like. If the person doesn’t fit that preconceived picture in your mind, then you see all kinds of gaps. But if you see the person for himself or herself, and accept the person as a given, without reference to an outside standard, then the picture becomes whole. The person is simply a person, on his or her own terms—nothing more and nothing less.

If you begin with an idea of “normal” that says that a person should be able to speak by the age of two like “normal” children, enjoy the same kinds of activities as “normal” adults, and socialize in a “normal” fashion, you’ve got a seriously complex, preconceived image of what it means to be a whole person. It’s nearly impossible that any atypical person could even begin to approach that image of normal. When we don’t, some of us are told that we’ve got pieces missing. Autistic people are told that we lack empathy, theory of mind, central coherence, and the ability to live as social beings—which, by the by, is all complete and utter bullshit, just in case you were wondering.

So who gets to decide what picture is normal? Other people who have the privilege of defining themselves as normal, that’s who. It’s a nearly invisible privilege for the most part, because it’s everywhere. It’s taken me a long time to see it and, ironically enough, I’ve begun to see it by virtue of what is missing from the language of many of the non-autistic people who talk about us.

Two words are missing from the statement “My autistic daughter is such a puzzle”—two little words that would change that sentence from an expression of privilege to an expression of a personal experience. And those two little words are to me. If someone were to write, “My daughter is such a puzzle to me,” then we’d be getting somewhere. All it takes is the inclusion of the personal pronoun. Of course, there is still that little issue of the puzzle metaphor, which runs the risk of portraying the child as a series of pieces, but at least the source of the fragmented perception would stay where it belongs: in the eye of the beholder. The speaker would be taking responsibility for describing his or her own limited perception rather than an objective fact.

Another example of this limited perception appeared on a recent blog by a parent who said that her autistic child is afraid of things “that just aren’t scary.” She didn’t say “that just aren’t scary to me.” She said, “that just aren’t scary,” as though there were an objective measure of what’s scary. These words imply that somewhere in the far reaches of the universe, there is some ideal called scary, we all know what it is and, if we’re scared of things that don’t measure up to that ideal of scary, something is terribly wrong. Now, I have always assumed that being frightened was a subjective experience, and that an image or a situation that frightened one person might not frighten another. I have never assumed that what went on in my own mind was exactly the same as what went on in other people’s minds. Far from it.

But wait a minute. I remember reading somewhere that being able to understand that other people think differently than I do is called having Theory of Mind (ToM). So, miracle of miracles, I actually have ToM, autistic though I am! And when a non-autistic person can’t imagine why an autistic person might be afraid of something, that non-autistic person seems to lack ToM. I see evidence that non-autistic people lack ToM regarding autistic people all the time. In fact, I see it in the work of “experts” on autism, and yet rarely does anyone call them on it. Usually, the ones who do the calling out are autistic people like me, who by definition don’t understand ToM, so we’re dismissed before we begin.

And once we’re dismissed, people can own the discourse about us and say just about anything they want. Consider the following:

A non-autistic person says that the world of an autistic person is a puzzle. That statement is taken as objective truth by most non-autistic people. In fact, it is irrefutable evidence that the person speaking is “normal” and that the person being spoken of has a “disorder.” All too often, family, friends, teachers, and professionals look at the autistic person, shake their heads, and say, “Yes, you’re right. Poor thing. He certainly is a puzzle!”

An autistic person says that the world of neurotypical people is a puzzle. That statement is taken as a purely subjective perception by most non-autistic people. In fact, it is irrefutable evidence that the person speaking has a “disorder” and that the people being spoken of are “normal.” All too often, family, friends, teachers, and professionals look at the autistic person, shake their heads, and say, “Poor thing. He’s so impaired. He just doesn’t understand us.”

Could the arbitrary nature of privilege be any clearer when one set of people has “understanding” when they don’t understand, and the other set of people is “impaired” when they don’t understand? Maybe it’s that I’m autistic, or a born democrat, or hopelessly addicted to fairness, but I find this kind of imbalance deeply disturbing and painfully unjust.

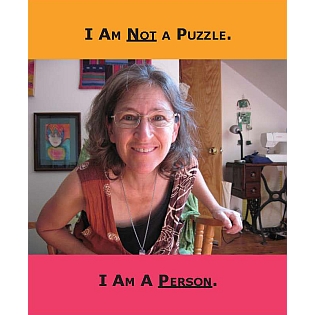

So what do I do when I meet the puzzle metaphor? Well, obviously, I write about it. And yet, the best response to it I’ve seen is a photo on the blog of my friend Elesia Ashkenazy. I’ve taken her lead and created a sign of my own [see above ].

If you want one, send me a photo by email and tell me what colors you’d like for the top and bottom, and I’ll make you your own sign. And if you’re comfortable with my publishing it on my blog, let me know. I’d love to have a post filled with signs like this, but only if people are comfortable with their faces being out there for the world to see. I do not “out” people, and I never will.

Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg can be reached via the email address available at her blog, Journeys With Autism, where On Puzzles, Privilege and Missing Pronouns first appeared.

Rachel is the author of The Uncharted Path: My Journey with Late-Diagnosed Autism, recently reviewed here.

Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg on 08/27/10 in featured, Language | No Comments | Read More