Recovery from JSD–My family’s journey

When my husband and I were about to become new parents, we were typically excited, and also typically naive. We fantasized about our new family and the life our daughter, Serenity Grace, would have. As healthy, able-bodied people ourselves, we had no reason to consider that we could become what was euphemistically called a “special-needs” family.

When my husband and I were about to become new parents, we were typically excited, and also typically naive. We fantasized about our new family and the life our daughter, Serenity Grace, would have. As healthy, able-bodied people ourselves, we had no reason to consider that we could become what was euphemistically called a “special-needs” family.

I realized something was wrong a moment after she was born. She wailed and flexed her hands, her head flopped back. Except for the odd twitching and the primitive animalistic noises she made, she could have been comatose. I spoke to her, and she didn’t respond. Placed on the floor, she could not walk, or even stand. Even in a chair, she could not sit up. She was limp, weak, completely nonverbal and nonresponsive. Her doctor told us this was normal and that she would grow out of it. I knew better. Something was horribly wrong, and I needed answers. I took Serenity Grace to an alternative health practitioner, who, after carefully observing her in his office, gave us the news that would change our lives forever.

He diagnosed her with Infancy Syndrome (IS), the most profoundly disabling category of Juvenile Spectrum Disorders (JSDs). Like most healthy people, I had never heard of Infancy Syndrome, but I soon learned that up to 100 in 100 births involved some form of JSD, making it the largest epidemic in history. IS sufferers are very small and physically weak. They cannot walk, talk, stand, bathe or toilet themselves, or even chew food independently. They are so severely handicapped that intelligence testing is difficult and sketchy, but they are generally considered to be profoundly intellectually impaired. They frequently scream, and often sleep only in short spurts (stories of being kept awake all night by an IS sufferer are common among caregivers). It is impossible for people with IS to live independently; all of them require round-the-clock care. Caring full-time for an IS sufferer is one of the most trying tasks of anyone’s life. Doctors are not sure what causes JSDs, but it is suspected to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There is no known cure for JSDs.

My heart sank as I learned these facts. My daughter was profoundly ill and no one knew why. Because JSDs are so little-known, in spite of their prevalence, adequate research on treatment options has not been done. Our doctors cautioned us that all treatments were considered experimental, and there was no guarantee of results. But I was willing to try anything to give my girl a chance at some semblance of a normal life. We started with behavior modification, the most established and widely-used treatment (there is evidence of its use in the treatment of what are now recognized as JSDs throughout human history), but because of the severity of Serenity’s IS, it was of little use. I turned to the internet for answers. There I learned about a new alternative treatment from a group called Defeat Infancy Now. It involved multivitamins, herbal supplements, frequent colon cleanses, and a powerful all-natural medicine called hydrogen hydroxide.

Almost immediately, we noticed improvements. Within weeks of beginning the DIN regimen, Serenity began holding her head up, making eye contact, and smiling. She began screaming less and sleeping for longer stretches. I wept with joy and gratitude the day she sat up on her own. A cascade of milestones followed—crawling, babbling, standing, eventually taking first steps on her own and tentatively speaking real words. The DIN protocols brought truly miraculous recovery. A year after we had begun treatment, Serenity’s doctor upgraded her diagnosis from IS to Childhood Syndrome, a milder, higher-functioning form of JSD. People with CS, though still significantly impaired, are often able to walk, talk, and, with proper supervision and assistance, manage basic self-care. When we learned that Serenity might have hope of having conversations with us, being toilet-trained, even reading and spelling, I knew that our DIN specialists were truly angels doing the work of the Divine.

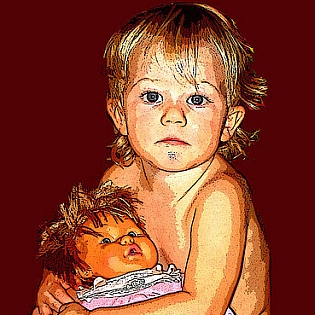

Our journey was still not an easy one. As Serenity Grace progressed, her behavior problems worsened. Her doctors told us this was a natural response to her body’s purging itself of toxins. We had to intensify her behavior modification regimen to 12 hours a day, add supplements of lavender essence and moondrops, and triple her dosage of hydrogen hydroxide. She became obsessed with imitating the behaviors of healthy people, even carrying around a replica of a person and pretending it was an IS sufferer, miming caring for it. It was heartbreaking to watch, but her therapist told us it was her way of processing the trauma of her own IS recovery. Her doctors urged patience, diligence, and hope. Some days she progressed more than we ever thought possible. Some days there were setbacks. We prayed every day for a full recovery, and never gave up hope.

Today, more than a decade after that first fateful day, Serenity Grace is a changed person. She is reading, writing, even cooking. In conversations, an untrained person can scarcely detect that she is handicapped. Her doctors believe that if she continues to recover, her diagnosis may soon be upgraded to Adolescence Syndrome, the mildest and highest-functioning form of JSD. They tell us that people with AS are sometimes, with proper treatment, able to lose their JSD diagnosis altogether. Some are even capable of employment. However, our fight is far from over. We have sold our house and all our assets to pay for Serenity’s treatments, and we are now on the brink of bankruptcy. Hydrogen hydroxide can cost over $15 an ounce, which, because JSDs are not recognized disorders, is not covered at all by our insurance. The care and treatment of people with JSDs can often plunge a family into dire poverty.

In spite of these clear hardships, JSDs remain controversial diagnoses. Some claim that JSDs are not disorders at all, but are normal phases of life that all healthy people go through. There are even JSD sufferers (or “kids” as their community has taken to self-identifying) who say that they are happy as they are and do not wish to be changed. Their claims may, I suppose, have some merit in the cases of very high-functioning sufferers of Adolescence Syndrome (a few of whom are nearly indistinguishable from healthy people, except for certain propensities to impulsivity and sullenness). However, these assertions could never be reasonably made about people suffering with severe Infancy Syndrome, as Serenity Grace was before we began treatment. No one could look at her as she was—limp, helpless, nonverbal, immobile, soiling herself, completely dependent—and call that a “normal, healthy stage of life.”

Juvenile Spectrum Disorders are treatable if caught early. But families need help. We need funding, care options, research, better treatments, and most of all we need a cure. We will not stop fighting until no families have to suffer as we have. Daily progesterone supplements are believed to prevent new JSD cases with over 99% efficacy, but millions of new JSD sufferers are born every day. Please pledge your support to your local chapter of Infancy Speaks, and march with us as we demand answers in our annual Walk For Juveniles. With hope, all things are possible.

adkyriolexy blogs at Kyriolexy.

Recovery from JSD–My family’s journey appears here by permission.

[image via Flickr/Creative Commons]

Guest on 04/26/11 in Autism, featured | No Comments | Read More